As day broke, I crawled out of the tent into a world thick with smoke,

more smoke by far than we’d experienced during our first two days of hiking. A ranger we’d passed the previous afternoon

had ensured me that the Aspen Fire, the raging monster creating all that

airborne soot and ash was still more than seventy trail-miles away from my

family, burning southeast towards Mammoth Lakes. We were heading that way, but we were almost

two weeks away, and fire crews were making progress towards containing the

flames.

I shook my head and tried unsuccessfully to stretch the stiffness from

my body. The fire sure smelled closer

than that, like we’d been sleeping inside some giant barbeque pit. My throat turned scratchy. My eyes burned. And all the doubts that had plagued me, the

ones that questioned whether or not an everyday Joe like me could really

navigate more than two hundred miles of Sierra wilderness with two elementary

school kids, flared up all over again.

I’d imaged how healthy it would be for my boys to get away from San

Diego and breathe clear mountain air for a month. But this was like sucking on a muffler and

walking up Interstate 5. Was it even

safe for my kids to be out here? Kai had

flirted with developing honest-to-goodness asthma since he was a baby. Was this going to push him over the edge?

The sun climbed over the distant mountains like some orange-pink ball

of fire in the sky. It was beautiful in

an alarming, post-apocalyptic sort of way, and it meant we’d have to reconsider

everything in Tuolumne Meadows. Maybe

this wasn’t our summer to hike the John Muir Trail. Maybe it had all been too much to bite off

anyway. Those thoughts left me feeling

dark and hazy like the sky as I scowled at the eerie sun and walked over to

pee on a bush.

The sun climbed over the distant mountains like some orange-pink ball

of fire in the sky. It was beautiful in

an alarming, post-apocalyptic sort of way, and it meant we’d have to reconsider

everything in Tuolumne Meadows. Maybe

this wasn’t our summer to hike the John Muir Trail. Maybe it had all been too much to bite off

anyway. Those thoughts left me feeling

dark and hazy like the sky as I scowled at the eerie sun and walked over to

pee on a bush.

There was nothing easy about that morning. We climbed more than two thousand feet while

smoke antagonized our throats and lungs.

The kids blew their noses more than normal, and their snot came out

black. At one point, just before midday,

as we trudged up a relentless series of switchbacks, Kai hit a wall. He’d had it.

He sat down heavily beside the trail and his body just sank onto the

rocks. He didn’t say much; he’d never

been the kind of kid to whine a lot. But

you could read his face like an open book.

Everything about that moment sucked for him. He didn’t want any part of any of it. He hated it.

We stopped and sat near him. I

pulled a Jolly Rancher from my pocket (part of a small stash I’d brought to

bolster the kids in tough moments), and unscrewed a water bottle for him. “You can do this, buddy.”

But it was Pam that really helped him, her unorthodox creativity, her ability

to commiserate before attempting to bolster.

“This hill sucks. Tell you what,

when you make it to the top you can say one cuss word as loud as you want.”

His eyes lit up. He nearly

choked on his Jolly Rancher.

“Just one,” she clarified and smiled at him. “After you make it.”

“As loud as I want?”

“As loud as you want.”

I looked at the two of them and laughed. It was ridiculous. It was questionable parenting… and it worked

brilliantly! We rested for a few more

minutes, passing around a water bottle, and when I said we should probably push

on Kai was the first to shoulder his pack.

We couldn’t see the crest of the hill for a long time. It just went up and up through the trees,

switchback after switchback. But eventually

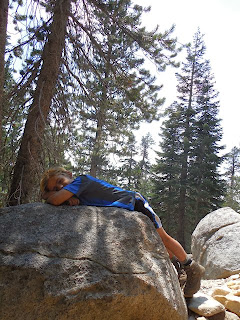

the climb ended on a wide ridge topped with the kind of boulders Fred

Flintstone and Barney Rubble used to build their homes. A breeze had kicked up, cooling our skin and

dispersing some of the smoke. They sky

was actually shifting from gray to blue.

Dozens of fritillary butterflies floated around us, their wings a

brilliant yellow-orange with black spots.

I took off my pack and inhaled deeply of the somewhat less hazy air,

not paying much attention to Kai as he climbed to the top of the tallest

rock. He spread his arms, the wind tousling

his hair, and he yelled with all his might.

I took off my pack and inhaled deeply of the somewhat less hazy air,

not paying much attention to Kai as he climbed to the top of the tallest

rock. He spread his arms, the wind tousling

his hair, and he yelled with all his might.

Of course I couldn’t know it then, but that was a turning point for Kai

and for our journey. Our strategy had

admittedly been irreverent. We’d let our

son yell the holy mother of curse words at the top of his lungs from a mountain

ridge. But it worked. The smoke, while lingering for several more

days, diminished steadily, and our son gradually grew stronger.

That afternoon the wind continued to sweep soot from the air, and by

the time we reached camp for the night the sky was blue with a scattering of

soft, white clouds. I pitched our tent

on a narrow shelf of rock, the door facing east so we could watch the sunrise

through the screen as we woke the next morning.

Then I went to filter water and soak my feet in a small stream that ran

playfully off the side of Sunrise Mountain.

Wildflowers grew like scattered pieces of rainbow in a meadow beside the

creek, and as I let the water numb my feet I picked a few stalks of wild onion

and chewed them.

The boys played, running across wide slabs of granite that sloped haphazardly

for several hundred feet before reaching the Cathedral Fork of Echo Creek. They ran as if we’d never hiked at all, as if

they’d never been tired or cussed a hill.

But eventually they settled in the shade of a juniper tree and entered

some imaginary world of their own creation.

You could tell by their faces, by the way they lingered together without

finding something stupid to argue about, that the imaginary world they’d

created was a cool place, somewhere worth spending time.

After dinner we lit a small fire and sat beside it as I read another

chapter of The Hobbit out loud. The sun set, enlivening Matthes Crest and a

million small peaks around our campsite with alpenglow. The wind had died, the first stars visible in

the eastern sky, and as I watched the sky darken something inside me started to

give way—some uncomfortable structure that I’d built inside myself over the

previous two decades of career and trying to be a grownup and struggling to

keep my family’s heads above water financially.

It was a structure that I’d hardly paid attention to really, but it

framed my mind and stretched down into my body.

It poked my lower back, slumped my shoulders and made me want to pop my

neck all the time. It was a structure I’d

built unintentionally each day while sitting in my cubicle, racing home on the

interstate with a millions other rats, and opening the mortgage statement to

wonder how we could manage it.

After dinner we lit a small fire and sat beside it as I read another

chapter of The Hobbit out loud. The sun set, enlivening Matthes Crest and a

million small peaks around our campsite with alpenglow. The wind had died, the first stars visible in

the eastern sky, and as I watched the sky darken something inside me started to

give way—some uncomfortable structure that I’d built inside myself over the

previous two decades of career and trying to be a grownup and struggling to

keep my family’s heads above water financially.

It was a structure that I’d hardly paid attention to really, but it

framed my mind and stretched down into my body.

It poked my lower back, slumped my shoulders and made me want to pop my

neck all the time. It was a structure I’d

built unintentionally each day while sitting in my cubicle, racing home on the

interstate with a millions other rats, and opening the mortgage statement to

wonder how we could manage it.

The structure didn’t break that evening, but I noticed it. I questioned it. And it cracked a little.

Read the full series by clicking on the links below:

Day 1 – Day2 – Day 3 – Day 4 – Day 5 – Day 6 – Day 7 – Day 8 – Day 9 – Day 10 – Day 11 – Day 12 – Day 13 – Day 14 – Day 15 – Day 16 – Day 17 – Day 18 – Day 19 – Day 20 – Day 21 – Day 22 – Day 23 – Day 24 – Day 25 – Day 26 – Day 27 – Day 28 – Day 29 – Day 30 – Day 31 – Day 32 – Day 33 – Day 34

Day 1 – Day2 – Day 3 – Day 4 – Day 5 – Day 6 – Day 7 – Day 8 – Day 9 – Day 10 – Day 11 – Day 12 – Day 13 – Day 14 – Day 15 – Day 16 – Day 17 – Day 18 – Day 19 – Day 20 – Day 21 – Day 22 – Day 23 – Day 24 – Day 25 – Day 26 – Day 27 – Day 28 – Day 29 – Day 30 – Day 31 – Day 32 – Day 33 – Day 34

J.S. Kapchinske is the author of Coyote Summer